- Home

- Paul Jennings

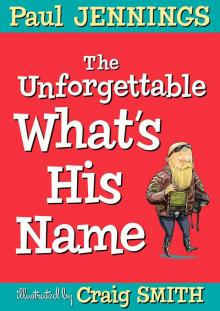

The Unforgettable What's His Name Page 5

The Unforgettable What's His Name Read online

Page 5

‘I was a bear,’ I said.

‘What?’ said Mum.

‘Whenever people stare at me,’ I said, ‘I get nervous. And then I blend in like a chameleon. At first it was just blending in. Like bark on a tree. And then I started changing. I grew a beard like a bikie’s.’

Mum’s look changed. She thought I was up to something.

‘You grew a beard? I don’t think so.’

‘I did,’ I said. ‘But now it’s worse. I actually turned into a bear. I was a copy. A real copy of Bad Bear.’

‘You didn’t frighten Gertag with Bad Bear, did you?’ said Mum. ‘You didn’t pretend that Bad Bear was real?’

She was beginning to get cross. She thought I had scared Gertag on purpose.

I could see that she didn’t believe me but I kept going. It was time she knew about my problem. I needed help.

‘You know I get shy. At school I don’t speak. I just listen. I don’t like it when people look at me. I don’t like it when teachers ask me questions. Gertag knows what I’m like. She calls me What’s His Name.’

‘She shouldn’t do that,’ said Mum. ‘But you don’t really change. You just …’

She was searching for words to describe it.

‘… blend in,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ I shouted.

‘Not like a chameleon,’ she said quickly. ‘Not like that. You sort of shrink down. You don’t meet people’s eyes. You are just very, very shy.’

I met her eyes. I didn’t even blink.

‘I was a bear,’ I said.

Mum shook her head and tried not to look cross.

‘Show me,’ she said. ‘Do it now. Go on. Copy something.’

‘I can’t,’ I said. ‘I can’t make it happen. I only change when I’m scared.’

‘Boo,’ said Mum in a loud voice.

‘That’s no good,’ I said. ‘I’m not scared of you. But if other people look at me I start to get hot and cold and shiver and then I blend in and they can’t see me.’

I started to cry. ‘I hate it,’ I sobbed. ‘I just want to be normal. Like everyone else.’

Mum stroked my forehead. And gave me a cuddle.

‘We will get help for you,’ she said. ‘The doctor. Or school counsellor. They will explain it to you. They will help you understand that you were not a bear. It was just a nightmare. Go to sleep. I’ll sit here until you do.’

It was no use. She would never believe me. I snuggled under the doona. Mum turned down the light and held my hand.

I tried to fall asleep but I had never felt more alone. Even with Mum there holding my hand. I was too worried about what was happening to me. And I couldn’t stop thinking about Banana Boy and the other monkeys that had escaped from the zoo. They would be hungry and cold. I had to find them. I had to do something. But I needed help.

‘I wish I had a dad,’ I said to Mum.

‘You do have a dad,’ she said. ‘You know that.’

‘I can’t even remember him,’ I said.

‘He remembers you,’ said Mum.

I looked at the photo of him holding me when I was only three.

He was standing in the backyard of our old house. The place where we lived before he left me and Mum. He was handsome. He had thick black hair and was wearing bathers. He had me in one arm and a cat in the other.

‘Where is he?’ I said.

‘I’m not quite sure,’ said Mum. ‘He’s gone up north somewhere.’

‘Why can’t I see him?’ I said. ‘Where is he? Why doesn’t he ring us?’

‘I’ve told you a hundred times,’ said Mum. ‘He had a problem. An illness. He was terrified of spiders. He thinks it stops him being a good father. He said he will come and see you if he ever gets over it.’

‘Everyone’s scared of spiders,’ I said.

‘Not like him,’ said Mum. ‘There’s a bit I haven’t told you. Something bad happened.’

‘What was it?’ I said, but Mum was quiet. ‘Tell me,’ I said.

Mum sighed. Then she started to talk. Her voice was soft, like the radio turned down low. She gave my hand a little squeeze.

‘You were only three,’ said Mum. ‘So you won’t remember what happened. Your dad took you to the park to feed the ducks. A spider ran up his leg. Inside his jeans.’

‘What happened?’ I said to Mum.

‘He started jumping around and yelling,’ said Mum. ‘He was terrified. He tore off his pants and shirt and started whacking at his back trying to get rid of the spider.’

‘Then what?’ I said.

‘You got scared and backed away. You fell into the lake. You were drowning but he didn’t see you. He was too busy trying to get rid of the spider. A girl jumped in and saved you.’

‘What girl?’

‘A teenager, from the high school. Her photo was in the local paper. She was a hero.’

‘What about Dad?’ I said. ‘Was he in the paper too?’

‘Yes,’ said Mum. ‘He was ashamed. He felt like a coward every time he looked at you.’

‘It was my fault,’ I said.

‘No, it wasn’t,’ said Mum. ‘It wasn’t anyone’s fault.’

I put my hand up and touched her face. It was wet.

‘Is he dead?’ I said.

‘No, don’t be silly,’ said Mum. ‘He sends me money. And I send him pictures of you.’

‘I want him back,’ I said.

‘So do I,’ said Mum. ‘He said he will come back when he is better.’

She had a faraway look in her eyes. I tried to cheer her up by changing the subject.

‘I’ve got a new friend,’ I said.

‘A new friend,’ said Mum. ‘Who?’

‘A bloke with a motorbike,’ I said.

‘A man?’ Mum did not sound pleased. ‘Who is he? How do you know him?’

‘He’s in a bikie gang,’ I said. ‘They’re new in town. They’re all really friendly. I knocked over their bikes and they let me off.’

Mum went quiet for a few seconds. I couldn’t tell what she was thinking. Was it ‘yes’ or was it ‘no’? ‘What does this man look like?’ said Mum.

I couldn’t tell her the truth. If I said that he was bald and had tattoos and earrings and a bushy beard she wouldn’t like it. So I lied.

‘He has neat hair and wears a suit,’ I said. ‘He’s a doctor. A brain surgeon.’

‘A bikie wearing a suit,’ said Mum. ‘Don’t give me that.’

‘He is a really great guy,’ I said.

‘He might be a good bloke,’ said Mum, ‘but …’ She let the words die. She didn’t seem to know what to say. But I knew what she was thinking.

‘He is too old to be your friend,’ she said. ‘You don’t know who he is. You can’t go around with a man.’

‘Why not?’ I said. ‘If I can’t have a dad, I can have a man friend, can’t I? It’d be good for me.’

I handed a piece of paper to Mum.

‘What’s this?’ she said.

‘His phone number. He told me to give it to you.’

‘Maggot,’ she shouted. ‘A brain surgeon called Maggot?’

Mum looked at me wildly. She was in shock.

‘I will be talking to Mr Maggot,’ she said. ‘That’s one thing for sure. You need a friend but his name isn’t Maggot.’

‘Or Gertag,’ I said.

‘Go to sleep,’ said Mum. ‘I’m turning off the light now.’ She sat there for a while and then crept out of the room and quietly closed the door.

I finally drifted off to sleep with thoughts of monkeys and spiders running around in my head. In the morning Mum had some news.

‘You were right,’ she said excitedly. ‘The monkeys from the zoo are in the news. They’ve all escaped and people are seeing them everywhere. You really did see a monkey.’

‘I told you that,’ I yelled. ‘I know him. Banana Boy.’

Mum looked at me sadly. ‘That bit was a dream,’ she said.

I sighed. ‘Well, I

’m glad the monkeys are not in the zoo. They can live in the trees with the koalas. They can go where they like. They can eat whatever they like.’

‘I wouldn’t be so sure about that,’ said Mum. ‘I don’t think they eat gumleaves.’

‘They like bananas,’ I said.

‘Bananas don’t grow in Victoria,’ said Mum. ‘It’s too cold.’

‘They’ll be hungry,’ I said. ‘Really hungry.’

She nodded.

I wondered how Banana Boy had arrived at my window. He must have followed his nose. He knew my scent from the zoo.

‘I’m going out,’ I said. ‘I have to find Banana Boy.’

‘Not yet,’ said Mum. ‘You wait here until I go and check a few things out. Do the dishes and clean up your room. And stay home.’

‘Aw, Mum,’ I said.

She gave me one of those looks.

I knew not to argue. So I bit my tongue as she left the house. She was gone for ages. I did everything she said but I kept going out to the front gate and looking for her. I had to find those monkeys.

While I was waiting I filled up a bottle of water and grabbed a banana. I shoved them into my backpack. I was just about to nick off when Mum finally appeared at the end of the street.

I yelled out, ‘Can I go now?’

She waved. Was that a ‘yes’ or was it a ‘no’?

This time I didn’t wait to find out. I grabbed my pack and ran for it. I thought she called out but I pretended not to hear. I had to find Banana Boy. Before he died of hunger.

I walked down the street, keeping my eyes peeled. I looked up into the trees and on the rooftops but there was no sign of the monkeys.

Other people were also looking for the monkeys. Keepers from the zoo searched parks and riverbanks. I saw two policemen checking out a drain and gardeners scanning the tops of trees in the park. It was busy for a Sunday.

I really wanted to help the monkeys. But a dreadful thought kept creeping into my mind. I had turned into a copy of Bad Bear when I became nervous. Would I have this forever? Was I doomed to be different? Or would I grow out of it? I didn’t want to be noticed but I didn’t want to turn into something else either, that was for sure.

In front of me I saw two people from a TV station. A man and a woman were stopping people in the street and talking to them. The woman held a microphone. The man pointed his camera at me.

Oh, no. It was bad enough just being noticed. But to be seen on television would be the worst thing in the world. I quickly ducked behind a letterbox.

I started to pant. I went cold. Then hot. It was like I was drowning. I couldn’t get enough air. Not again. I was changing. It was happening again.

‘Where did that boy go?’ said the guy with the camera.

The cameraman was looking straight at me. But he couldn’t see me. Because there were two letterboxes by the side of the road.

And one of them was me.

I couldn’t believe it. I had turned into a copy of the letterbox. Oh, this was terrible.

I couldn’t see my own face but I knew that I still somehow had eyes and a mouth. I could see and I could breathe.

An old lady approached. Oh, no, no, no. She was holding a bunch of letters. She walked towards me. Then she lifted up my mouth flap and started to stuff a letter into it.

‘Argh.’ It hurt. All smooth and sharp.

The old lady became angry.

‘It’s blocked,’ she said. ‘Nothing works these days. The country is going to the dogs.’

She pulled the letter out of my mouth slot. Then she shoved it into the letterbox standing next to me. The real one.

‘Where did that kid go?’ said the cameraman.

The old lady pointed at me. ‘There’s something stuck in there,’ she said. ‘It might be a monkey.’ She gave a little snort.

‘A monkey couldn’t get through the flap,’ said the cameraman.

He walked over towards me. I was nothing more than a red box with a slot for a mouth. He pushed my mouth flap open and stared in. It was like being at the dentist’s.

‘Pooh,’ he said to his friend. ‘That letterbox has got bad breath.’

I could hear them laughing as they walked away down the street.

The old lady left, and I was still frozen to the footpath.

Life was not good.

It was driving me crazy. I couldn’t just stay there all day like that. Waiting for the copy effect to go away.

‘Think. Think, think, think.’

I had to relax. I had to get rid of the fear. I had to be able to let people stare at me. And not care about it.

‘Relax, relax, relax,’ I said inside my head. ‘Relax, relax, relax.’

After a bit I could feel something happening. Yes, yes, yes. A warm feeling swept through my hard steel body. My arms came back. And my hands. Soon I was me again.

My time as a letterbox was over. I had all my bits. Just to be on the safe side I looked inside my pants. Yes, everything was there.

Relaxing had done the trick. It definitely seemed to be the secret. If I could relax, I could beat my fear.

I walked on, thinking about my father and keeping an eye out for the monkeys.

I stopped at a public toilet. I decided to go and see if any monkeys were hiding in there. But then I had a nasty thought.

What if I went into the toilet and something gave me a fright? I might turn into a copy of something. A hand basin. Or a toilet bowl.

What if I was a toilet bowl and someone walked in and sat …? No, no, no. I couldn’t bear to even think about it. Horrible, horrible, horrible.

I pushed the thought out of my mind and kept going down the street. At that moment I heard a sound. A welcome sound. Motorbikes.

It was Granny and Shark and The Chief and Metal Mouth. And Maggot.

They pulled up with squealing brakes and killed their engines.

‘It’s our mascot,’ yelled Maggot. He held up his hand and gave me a high five.

Granny sat on her three-wheeler like a queen. Sandy was perched on the back.

Maggot gave me a big smile.

‘Hey, mate,’ he said. ‘What’s new?’

I couldn’t look him in the eyes. ‘Mum won’t let me see you,’ I said.

There was a long silence.

‘She says you’re too old. And she doesn’t like maggots.’ The last bit was a lie. I was just trying to make him feel better.

That’s when I noticed that they were all grinning.

‘She has already paid us a visit,’ said Granny. ‘This morning.’

‘And I’m invited over for tea,’ said Maggot.

I couldn’t believe it. They were all nodding. Was it true?

‘She’s cooking her special stir-fry.’

I sort of groaned and whooped at the same time. Mum had really invited him for tea. It was great news. She must have been feeling really sorry for me. Because I had no friends. Maybe she heard Gertag calling me What’s His Name.

But Mum’s stir-fry? Poor Maggot.

‘What are you up to now?’ said The Chief.

‘I’m looking for the monkeys,’ I said. ‘They’re my friends. And they’re hungry.’

They didn’t seem to know what to say.

‘Better leave it to the experts,’ said Metal Mouth. ‘Monkeys have sharp teeth.’

I had to get them on side.

‘We have to get them to a safe place,’ I said. ‘Into the bush. If the rangers come they will try to take them back to the zoo.’

Maggot clapped a hand on my shoulder. He looked at me seriously.

‘What’s it like for them at the zoo?’ he said slowly. ‘Their pen. What’s it like?’

I knew the answer to that. So did he. ‘It’s really big, with trees and nets to climb and stuff like that.’

‘What’s the food like?’

‘Good, plenty of bananas,’ I said.

‘What if they get sick?’

‘They have vets,’ I said.

‘There are not many of those monkeys left in the wild,’ said Maggot.

‘Can’t they go back?’ I said.

He shook his head.

‘Where they came from the forests have all gone,’ he said. ‘One day, maybe. When the trees have grown again.’

‘We have forests,’ I said.

‘Wrong trees,’ he said. ‘There’s nothing they can eat.’

We stared at each other.

I spoke slowly. ‘They have to go back to the zoo, don’t they?’

‘They do, mate,’ said Maggot. ‘They do.’

‘But they’re scared,’ I yelled. ‘The monkeys might scatter. And get lost. And never find each other again. They will just run away. They don’t like all the noise. They might get hurt. You have to help me get them back to the zoo. Now.’

Maggot looked at me with a kind grin. ‘How could I do that, mate? We don’t even know where they are.’

I pulled out the banana I had in my backpack.

‘That won’t go far,’ said Metal Mouth.

‘I know,’ I said. ‘But I’m going to Franky’s Fruit Stall to buy some more.’

I put my hand in my pocket and felt the coins I had in there from yesterday, when people thought I was a busker. I held them out.

Maggot smiled and then nodded knowingly to the others. ‘We have to go,’ he said. ‘Stay cool, man.’

The five of them started their engines and disappeared in a cloud of smoke and noise.

‘You stay cool too,’ I yelled.

I walked on down the street, still looking for the monkeys. There was no sign of them, so I headed out into the countryside.

It took me ages to get to Franky’s Fruit Stall. It was way out of town.

My heart sank when I finally got there. There was a sign on the window.

CLOSED. BACK LATER.

Rats. I stared through the window. There were plenty of bananas. But the place was locked up.

That’s when I noticed it. Monkey poo. All over the place. The monkeys had been there but they couldn’t get in.

Unbearable!

Unbearable! Unreal Collection!

Unreal Collection! How Hedley Hopkins Did a Dare...

How Hedley Hopkins Did a Dare... A Different Land

A Different Land The Nest

The Nest Uncanny!

Uncanny! The Unforgettable What's His Name

The Unforgettable What's His Name Paul Jenning's Weirdest Stories

Paul Jenning's Weirdest Stories Unreal!

Unreal! Paul Jenning's Spookiest Stories

Paul Jenning's Spookiest Stories Uncovered!

Uncovered! Paul Jennings' Trickiest Stories

Paul Jennings' Trickiest Stories A Different Boy

A Different Boy Unbelievable!

Unbelievable! Wicked Bindup

Wicked Bindup Don't Look Now 1

Don't Look Now 1