- Home

- Paul Jennings

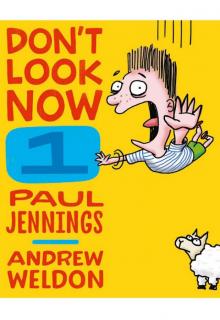

Don't Look Now 1

Don't Look Now 1 Read online

First published in 2013

Copyright © Text, Lockley Lodge Pty Ltd, 2013

Copyright © Illustrations, diagrams, handmade fonts, Andrew Weldon, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the

National Library of Australia: www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 123 3

eISBN 978 1 74343 102 3

Design by Andrew Weldon and Bruno Herfst

Set in 12 pt Dolly

To Nina & Millie Parker – PJ

Contents

Story One: Falling for It

1. Seeing Things

2. Trying Flying

3. Lifting off

4. Like a Bird

5. In a Hole

6. Telling Dad

Story Two: The Kangapoo Key Ring

1. Growing Pains

2. Seeing Things

3. The Joker

4. perfect Copy

5. Bird Brain

6. On the Road

7. A Sort of Smile

eople think I am weird. Even Mum (although she is nice about it). The kids at school basically avoid me. I spend most of recess hanging around on my own.

The other kids don’t see things the same way as me. I spend a lot of time imagining.

I just don’t get it. Inside my head I am not the same as other kids.

Like for example, once, our teacher Jenny took us all out onto the oval and told us to lie on our backs on the grass.

‘Look up at the clouds,’ she said. ‘Tell me what you see.’

We all stared up at the clouds in silence. There was so much up there. It was like a circus on a busy day.

Sean Green spoke up. ‘I see a duck,’ he said.

‘There’s a car,’ said Mahood.

‘I see a little bunny,’ said Mandy Chow.

‘They are all very good imaginings,’ said Jenny. ‘What about you, Ricky? What do you see?’

I told them what I saw.

‘There is a horse,’ I said. ‘It stands twenty-two hands high. A stallion, wild and free. The smaller clouds are the other horses. They follow him everywhere – they follow him anywhere. His name is Thundercloud.’

I was excited by the clouds. I went on, telling everyone what I saw.

‘Thundercloud has never been tamed,’ I said. ‘He leads his mob over the mountains. One flick of his tail can make lightning. His eyes are like burning coals from hell.’

When I had finished there was a long silence.

After a bit, Jenny said, ‘That’s very good, Ricky.’

No one else thought so.

Mandy Chow pointed to another cloud. ‘I see a lovely little bunny,’ she said. ‘Ricky’s horse sucks.’

She glared at me with half-closed eyes. She didn’t like me. No one seems to like me much. Especially girls. I don’t know why.

Our teacher smiled at me.

‘Do you see anything else, Ricky?’ she asked.

I did.

‘Weirdo,’ said Mandy Chow.

I just don’t get it.

What did I do wrong?

It was just a cloud.

ere is a list of things I am good at.

A cross means no good. A tick means excellent.

Being a dork gets a tick because that’s what I am.

There is one more thing I get a tick for on my self-report card. Oh, yes, I get a tick for flying.

And that’s because I can.

It started when I was a little kid.

I used to leap off anything I could find.

I wanted to fly.

I wanted to be up there with the birds, soaring around in the clouds and taking in the view. But I didn’t just want to fly – I wanted everyone to see me fly. I guess you could say I was nutty about it.

I wanted people to point up and say, ‘Look at Ricky. He’s flying.’ I wanted their eyes to bug out. I wanted them to faint with surprise.

I wanted to be …

Nothing ever happened though. Every time I jumped, I just dropped back to the ground.

So I tried it from the shed roof. I thought, ‘Believe in yourself, Ricky.’

Dad was always saying, ‘Go for it, Ricky. Nothing ever happens unless you take a risk.’

I climbed on top of the wall around our back garden and up onto the roof of Dad’s shed.

It was a long way down. I closed my eyes, yelled out, ‘Go Ricky,’ at the top of my voice and leapt forward with outstretched hands.

After I got out of hospital I decided on a new approach.

I tried using the power of my mind to lift myself up – levitation. I would screw up my eyes and try to fly just by thinking about it. I would imagine my feet slowly rising as I chanted. ‘Fly, fly, fly.’

It didn’t work. But I didn’t give up. Every day I would try again. ‘Fly, fly, fly.’

Mum thought I was crazy.

Don’t get me wrong. I love her. She is the best mum in the world and she mostly just rolls her eyes when she sees me trying to fly.

Once I was in the kitchen trying to fly. I screwed up my eyes and concentrated. I tried to lift my feet off the floor. Just by brain power.

‘Fly, fly, fly,’ I said aloud.

At that very moment Mum walked in. ‘What are you doing?’ she said.

‘I’m trying to lift my feet off the ground. I want to fly. Up in the air.’

Mum looked worried. ‘Have you talked to your father about this?’ she said.

‘I’m not strange,’ I yelled. ‘Dad said you can do anything if you try hard enough.’

‘Well, not everything,’ said Mum.

‘Is he a liar?’

‘No, he just gets carried away.’

‘I believe him,’ I said. ‘I’m going to fly.’

‘I don’t think that’s a good idea,’ said Mum.

‘I’ll bet you fifty dollars,’ I said.

‘You haven’t got fifty dollars,’ said Mum.

Mum has an answer for everything. It’s annoying. I waggled my finger at her like she does sometimes. ‘Dad always says, “Put your money where your mouth is.”’

‘No,’ she said. ‘I’m not going to bet. Instead of trying to fly, why don’t you try to clean up your room?’

‘For ten dollars?’ I said.

‘For nothing,’ said Mum. ‘It’s your room.’

‘I’m saving up to go to Water World and ride on the Super Sucker Water Slide,’ I said. ‘Every kid in my class has been to Water World except me.’

Mum snorted. ‘I must have heard that one about a million times before,’ she said. ‘But I’ll tell you what. If you stop this silly business of trying to fly I’ll take you to Water World.’

I thought about it. I thought about it really hard.

But I knew that one day I would fly. ‘No thanks,’ I said.

‘Okay, then,’ said Mum. ‘If you clean up your room every day for six months I’ll take you to Water World.’

&

nbsp; I thought about this offer for a long time. But I shook my head. The price was just too high.

Even for a visit to Water World and a ride on the Super Sucker. I couldn’t clean my bedroom every morning for six months. I just couldn’t do it.

Mum looked at me in a worried way and gave a big sigh.

I went up to my room and read my favourite comic.

freaked out. I was really doing it.

I was floating in the air above the beanbag. I screamed.

Then I smiled. And laughed. I could do it.

I could really do it. I was flying.

‘Woo hoo,’ I yelled. ‘Look at me. Look at me.

I can fly.’

Feet pounded down the hall.

Mum ran into the room, closely followed by Dad.

‘What? What? What?’ yelled Mum.

‘I flew. I flew. Did you see it?’

‘I saw you jump into the beanbag, Ricky,’ said Mum.

She had that worried look on her face. She must have thought I was losing my marbles.

‘No, no, I flew.’

‘Don’t try to fly,’ said Mum. ‘Join the football team or something sensible.’

‘No. I did, I did it, I flew,’ I shouted. ‘Watch this.’

Mum sighed.

‘Fly, fly, fly,’ I said to myself. ‘Lift off. Feet rise up.’

‘Stop it,’ said Mum. ‘You will do yourself an injury.’

‘I did fly,’ I said. But even as I said the words I started to have doubts. Was it a dream?

Was I going nuts? Did I really lift off the ground?

‘I did fly,’ I said. ‘My feet…’ The words trailed away.

‘I always wished I could fly, too,’ Dad said quietly.

‘Really?’ I asked.

He nodded.

‘Yes,’ said Mum. ‘And look what happened.’

‘What do you mean?’ I said.

‘Don’t,’ said Dad. But Mum tightened her lips, then kept talking.

‘It was when you were just a baby, Ricky. You know Mrs Briggs over the fence?’

‘Old Mrs Briggs?’

‘Yes. Her kitten got stuck up the flagpole in the front yard. She was crying something terrible and there was no one there to help. Except Dad. Mrs Briggs rushed inside to call the fire brigade and while she was gone Dad sprang into action.’

I stared at Dad with pride. ‘You climbed a flagpole to save a kitten? You are a hero, Dad.’

Dad blushed.

‘Except,’ said Mum, ‘that when Mrs Briggs came outside…’

‘Don’t,’ said Dad.

Mum didn’t take any notice of Dad blushing. She just went on with the story.

‘And your father was stuck up on top of the pole. He couldn’t get down.’

‘That’s enough, Mary,’ said Dad. ‘He doesn’t want to know all this.’

‘Yes, I do,’ I said.

Mum kept going. ‘Everyone in the street came to look. There he was – a grown man clinging to the top of a flagpole. By the time the fire brigade came to save him there were hundreds of people watching.’

‘Wow,’ I said. Dad gave a little groan.

‘We were a laughing stock. That cat saved itself and climbed down the pole. And your father got stuck. The whole country knew that he climbed a flagpole and couldn’t get down. That’s how well he could fly.’

She gave a little smile and then she added. ‘But I still love him.’

‘So do I,’ I said.

I do too. Dad’s a bit strange. But then, so am I.

Birds of a feather. That’s us.

he next morning I put on my backpack and walked slowly to school. I went through the park so that I could try once more.

I wanted to see if I could lift myself off the ground again with only the power of thought.

But I didn’t want anyone to see me going red in the face and groaning with the effort.

I stopped halfway across the park and sat on a bench. I thought about how amazing it would be to fly high up in the sky, not just a metre above a beanbag. I knew it would be fantastic. Up there like a bird.

I stood and checked out the park.

‘Fly, fly, fly,’ I said under my breath.

My ears grew hot. My eyes throbbed.

Slowly, slowly, I rose into the air.

Now I needed someone to see me. Now I needed someone to almost faint at the sight of my amazing powers. ‘Look at me,’ I shouted.

No one heard me. I yelled louder.

‘I’m flying, I’m flying.’

The words had no sooner left my mouth than I fell. I plopped straight down to the ground.

I closed my eyes and tried again. I strained and strained, but nothing happened.

I walked along the winding path. One more try.

I would give it one more go. There was nothing I wanted more than to get to school and show off my flying ability.

I concentrated really hard. And once again it happened. I looked around, but there was no one in sight.

The word ‘forward’ sprang into my mind. Slowly I began to move along the path hovering a few centimetres above the ground. ‘Higher,’ I thought. I rose about fifty centimetres more. I was floating along the path and my feet weren’t even touching the ground.

This was amazing. This was fantastic. Awesome.

It was like skating on ice except there was nothing under my feet but air.

I flew around a tree. I flew over a rubbish bin.

I felt as if my body was filled with helium. It was absolutely mind-blowing.

‘Hey,’ the gardener yelled. ‘Can’t you read?

Get off the grass, you little brat.’

I tried to make sense of it. Sometimes I could fly and sometimes I couldn’t. I needed to show someone. I needed someone to believe me.

Then everything would be okay.

A far off beeping noise sounded through the trees. It was the school bell. I was going to be late.

‘Up,’ I thought. Up I went. Not high. Just a little off the ground.

‘Forward,’ I thought. I flew forward.

‘Faster,’ I thought. I went faster.

I didn’t say the words aloud. I didn’t have to.

I just thought them. Brain power was enough.

Faster and faster I sped through the park, standing straight up and skidding forward like a bishop on a chess board. The feeling of speed and power and lightness was fantastic. I was dizzy with happiness.

I sped along in silence. My heart was thumping. This was my big chance. Everyone was going to see me fly. I would be a dork no longer. I would be the amazing flying boy. The school gate came into view.

There were kids gathered around staring at something on the ground. No one was looking at me. Except…

The little girl shook her head. She wasn’t sure what she had just seen. She joined the other kids who were all staring down into the ground. There was orange netting surrounding a deep hole where workers had been digging for several days.

But there were no workers. Only kids.

‘What’s going on?’ I said. No one answered me, so I looked for myself.

he poor little dog had fallen down the hole and was unconscious at the bottom. The little girl started to cry. It was a very deep hole.

‘Poor little doggy,’ she said.

Suddenly a voice sounded behind us. ‘Into school everyone. Quick. We will call the fire brigade.’

It was our teacher, Jenny. She picked up the little girl and headed for the school office.

Everyone shuffled away. Everyone except me.

I was alone at the edge of the hole.

‘Up,’ I said.

I floated up.

‘Forward.’ Now I was hovering over the hole.

This was scary. It was a long drop to the bottom.

‘Down,’ I said.

I began to descend.

Down,

down,

down.

It was dark and cold. I lande

d gently on my feet. The dog was lying on its side with its eyes closed. I picked it up and cradled it in my arms.

‘Up,’ I said.

Up I went. Up, up, up – nearly halfway.

Then…

Whoosh. Crash. Splash. I hit the muddy bottom. With a thump. My ankle was twisted and every bone in my body jarred. I groaned in agony. The little dog was still cradled in my arms. I could hear shouting and yelling from above.

What was happening? What made me fall? Suddenly it clicked.

‘I get it,’ I said to the dog. ‘Now I see.’

I took off my backpack and tipped out my books. I had to be quick. There was muffled barking, but I ignored it.

‘Up.’

Slowly I floated up. I stopped when my head was just below the top. I closed my eyes and gave myself an instruction. ‘Up, over the edge and down.’ That’s what I thought. And that’s exactly what happened.

Unbearable!

Unbearable! Unreal Collection!

Unreal Collection! How Hedley Hopkins Did a Dare...

How Hedley Hopkins Did a Dare... A Different Land

A Different Land The Nest

The Nest Uncanny!

Uncanny! The Unforgettable What's His Name

The Unforgettable What's His Name Paul Jenning's Weirdest Stories

Paul Jenning's Weirdest Stories Unreal!

Unreal! Paul Jenning's Spookiest Stories

Paul Jenning's Spookiest Stories Uncovered!

Uncovered! Paul Jennings' Trickiest Stories

Paul Jennings' Trickiest Stories A Different Boy

A Different Boy Unbelievable!

Unbelievable! Wicked Bindup

Wicked Bindup Don't Look Now 1

Don't Look Now 1